Sharad Kelkar: I-Day reminder of stories that need to be told to honour our history

Actor Sharad Kelkar, who is known for his roles in movies like ‘Bhuj:The Pride of India’, ‘Code Name: Tiranga’, among…

He was the only leader in India who was offered thrice the honour of the presidentship of the Indian National Congress and which he declined every time.

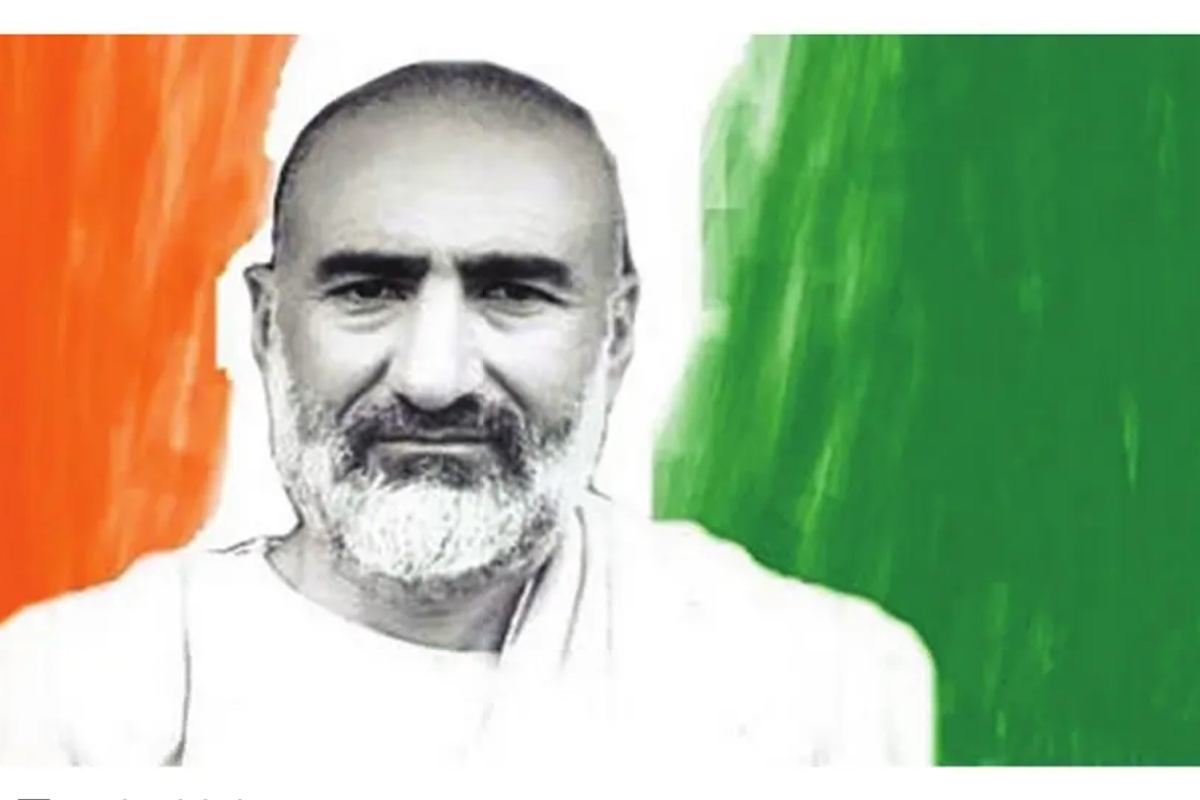

(photo:SNS)

He was the only leader in India who was offered thrice the honour of the presidentship of the Indian National Congress and which he declined every time. He is probably the most overlooked Muslim leader of non-violence in the world.

He belonged to one of the most intractable races on earth oozing sagas and memories of violence and bloodshed, yet he was a great apostle of peace and non-violence. During the freedom struggle, the organisation he formed lost a greater number of workers than most other parties fighting for independence. He fought for the freedom of his land; but when freedom came, it came with partition and he had to be away from Bapu, away from India and her people. He is Abdul Ghaffar Khan or Badshah Khan, whose death anniversary falls this month. His life and activities contain ingredients myths are made of.

In one sense, he is like Tagore’s Kabuliwala. Under compelling circumstances, both left the land of their prime-time activities with a heavy heart. Tagore’s Kabuliwala left India to go home to his loved ones, but Khan left this country for a life of disillusionment, sadness and extreme hardship, always under the gaze of suspicion of his own countrymen.

Advertisement

A seeker of peace, brotherhood and justice, Ghaffar Khan got the strength and inspiration for his struggle from his spirituality. His life stood as an example of how the might of determination could be stronger than that of the gun even in a society that was a serious victim of diverse forms of internecine violence. Compared by many to the mighty mountains of his rugged homeland, this giant of a man stood steadfast not for a specific political group, but for universal values of love and humanity.

In fact, as one of the greatest humanitarians of the 20th century, Frontier Gandhi epitomised the non-violent soldier who fought persuasively for human dignity. Nehru paid his tribute to this man in the following words: “When the history of the subcontinent is being written, perhaps only a very few of those who occupy public attention will find a mention in it.

But among those very few there will be the outstanding and commanding figure of Badshah Khan. Straight and simple, faithful and true, with a finely chiselled face that compels attention, and a character built up in the fire of long suffering and painful ordeal, full of hardness of the man of faith believing in his mission and yet soft with the gentleness of the one who loves his kind exceedingly.” Hailing from a well-to-do land-owner’s family in Peshawar, Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988) first understood the importance of education in the service to the community under the influence of Rev.

Wigram in Edwards Memorial Mission High School. His joined the Guides, an elite corps of Pashtun soldiers under the British Raj, but witnessing an incident where a family friend, also an army officer, was being insulted by a British officer, he opted out of the military out of anguish and disgust. The Pashtun society at that time was deeply wounded by colonial oppression, devastating violence and blood feuds.

Moreover, the situation was aggravated by the repression of the mullahs who told the people that if their children went to school, they would go to hell. The circumstances stirred up a determination in Badshah’s mind to overthrow the foreign rulers although he felt that the then Pashtun society, largely uneducated and violenceprone, could not achieve this mission. Education, he felt, would be the first step towards reform and empowerment.

Khan launched his first school in Uthmanzai and soon he was initiated into the circle of progressiveminded people. But the regressive authorities, fearing the influence of these people, started repressive measures and shut down the school. In the meantime, Khan got married and was blessed with two sons. But his wife’s death drew him into the arena of politics and he began his active political career by protesting the notorious Rowlatt Act in 1919 which was introduced to curb the so-called seditious activities in the country.

At Uthmanzai, Khan held a protest meeting which was attended by 50,000 people. But the provincial authorities arrested Khan immediately followed by a fine of Rs 30,000 upon the villagers of Uthmanzai. Khan left India for Afghanistan for a short time during the Khilafat movement as Muslims were told that they were not safe in British India.

But Khan soon returned to India to restart his social and educational activities in his hometown. With the support of likeminded Pashtuns, he embarked on preventing or at least reducing crimes in society as well as the pervasive use of intoxicants among his native people. Initiatives were taken to create awareness regarding modern education and promote Pashto language and literature in addition to inculcating true Islamic principles among the Pashtuns.

Under Khan’s inspiration a host of schools came up offering subjects like English, Mathematics and History side by side with a number of vocational skills like carpentry, weaving and tailoring. Education was free and the schools were open to all people irrespective of their religion. Badshah Khan toured his homeland extensively, connecting with people and sowing the seeds of nationalism amongst them.

When the Provincial Khilafat Committee was reconstituted, Khan was made its President. He also founded the Anjuman-i-Islam-ul-Afghania (Society for the Reform of Afghans). The rulers were prompt to jump into action sending Khan behind bars where he would be locked up day and night with his food shoved in through a barred opening in the door. The food was so bad that even dogs and cats around the prison refused to touch it.

Moreover, Khan had to grind twenty seers of corn every day on a grindstone. He bore all the hardships stoically. Khan’s political publication ‘Pakhtoon’ inspired the then king Amanullah Khan to come out with another publication ‘Jagh Pakhtoon’.

(The writer, a PhD from Calcutta University, teaches English at the Government-sponsored Sailendra Sircar Vidyalaya, Shyambazar, Kolkata)

Advertisement